Marcus D. Najera and Dennis Bark share the magic of a Stanford childhood

I just want to say to the Cardinal, I’m just one guy that you have inspired and influenced and really created from the ground up.

Sometimes I will actually drive back to Escondido Village, find the old apartment and sit … and remember being a kid and how awesome it was growing up here on the Farm.”

– Marcus D

Imagine life at Stanford without having to be admitted, publish papers, earn a paycheck or please a boss – just the pleasure of discovery and the joy of learning in surroundings designed for it.

Marcus D. Najera, the San Francisco FM radio host known as Marcus D of the Marcus and Sandy show, knows this pleasure well. As the son of a Stanford graduate student in the early 1980s, he was lucky enough to spend part of his childhood on the Farm, he said, and was forever changed by that.

“There’s so much knowledge here,” Najera said. “There’s something around every corner. Which, for me, was kind of a metaphor for life.”

As a residential university, Stanford is more than a school. It’s also a home for the hundreds of faculty, staff and student families who live on its lands. From the start, founders Jane and Leland Stanford encouraged on-campus living to build a community of learners.

Najera and other Stanford kids say they benefited immensely from an environment that was protective but broadening, safe but ripe for discovery, international in scope but united in purpose. They grew up taking the virtues of learning for granted. They looked up to college students as role models. They equated the pursuit of knowledge with play.

“To be honest with you, I didn’t know you could get around Stanford in a car, because we rode bikes so often,” Najera said. “We never drove. And frankly, we hardly ever left. Everything was here, so it was really fantastic.”

The Najeras lived in Escondido Village, a campus apartment district primarily for graduate students and their families. There, Najera said, “I had neighbors from all over the world.

“I was learning Hebrew one day. Learning Chinese another day. Learning how to kick a soccer ball from a kid I knew from Ethiopia who could kick it the length of a football field.

“That, plus the food. Everybody would bring their best dish, and it was fantastic.”

Marcus’ father, Daniel Najera, MA ’84, would load him onto the book rack of his bicycle and tote him to his classes at the Graduate School of Education. There, Marcus Najera learned to value precision in language, a lesson he says shaped his entire adult life.

“He had an amazing professor by the name of Robert Politzer, and they had a whole class on the ‘yuck’ phenomenon, the meaning of the word ‘yuck,’ and I just thought, ‘This is it, how do we take an hour to talk about that word? This is amazing.”

Thirty-five years earlier, before Escondido Village was built, another Stanford kid named Dennis Bark lived in the same part of campus with similar freedom and joy.

Five-year-old Dennis moved with his family in 1947 to Stanford, where his father, William Carroll Bark, had gotten a job teaching medieval history. The Barks first lived in a rundown former boys’ school on Stanford land off Alpine Road that young Dennis loved, because the long-gone pupils had left “the most elaborate tree houses … that I had ever seen.”

They soon moved to Escondite Cottage, an equally rundown but more distinguished home later rehabbed for Escondido Village’s administrative offices. Stanford students rented the top floor, and they rigged Dennis an enormous electric train layout and a climbing rope screwed into the two-story ceiling.

“We’d climb over the banister and shinny down it. It was great.”

Like Najera, Bark went to school on campus, and like him he found the experience stimulating and protective at the same time. “We all knew each other, and we were lucky because the university was basically our playground,” Bark said in an oral history conducted by the Stanford Historical Society.

“We felt safe. We never worried about anything. And it was a lot of fun, especially for children, because it really was a farm.”

The Bark kids hunted polliwogs and frogs in Lagunita. Near their home along Escondido Road was a dumping ground for debris from the 1906 earthquake. They dug up mosaic tiles from Memorial Church to put in their mother’s garden. On weekends, they snuck into the men’s gym to shoot hoops while campus police looked the other way.

“They managed to give real meaning to the word ‘tolerance,’ except when we acquired firecrackers, which we did on a regular basis,” Bark said.

Like Najera, Bark gravitated to the seeming glamour of the student union, though in his day it was housed in Old Union rather than Tresidder and the undergraduates he longed to emulate played jukeboxes rather than video games.

“Campus kids were welcome at the Old Union as long as they had enough money to pay for a milkshake. We … got to know some students who were also our sports coaches. We liked them and looked up to them, and if we wanted to see them, we could find them at the Union.”

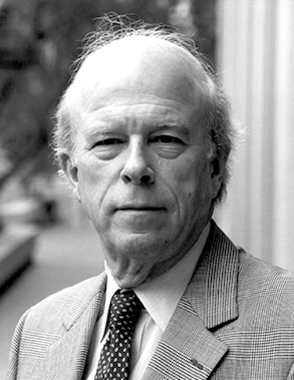

Bark liked Stanford so much that he aborted a college career in Iowa to return for his BA, graduating in 1964. Later, he became an expert in European political and diplomatic affairs, a Chevalier of the French Legion d’Honneur and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution.

“I have so many happy memories of growing up on campus, and I don’t have any unhappy ones,” Bark said.

“As children, we didn’t compare Stanford to anything else. We just knew it was wonderful.”

Read more about Dennis Bark’s Stanford childhood in the years after World War II.

Find ways children and teenagers can learn on the Farm through programs, mostly free for participants, coordinated by Stanford’s Office of Science Outreach.