New-student tradition sets the tone for intellectual life at Stanford

Every summer, incoming Stanford undergraduates look forward to getting a big parcel in the mail. It’s not the thick envelope full of forms and brochures that for decades signified college admission.

Rather, it’s a parcel of books – three books. They offer entrance to the intellectual climate of Stanford, with its heady mix of readings, collaborations, new friends and new ideas.

Stanford’s Three Books program is a New Student Orientation tradition. Each year, a faculty moderator selects three books for incoming students to read and discuss online over the summer. When students arrive in September, they attend a discussion with the authors and have a chance to meet them. It’s an important moment for students, the first and one of the only times before Commencement when they’ll all be together. Afterward, they repair to their dorms for group discussions led by resident staff.

“The Three Books program creates a common intellectual experience that sets the tone for what will be their home for the next several years,” said political science Professor Scott Sagan, who made the 2011 selections.

Each year has a theme touching on challenges life may offer, both at Stanford and beyond, and the skills and values students can use to meet them. Three Books engages new students with tales of crisis and resilience, ethics and choice, war and justice. It shows them that Stanford is not just a place to acquire academic or professional knowledge, but also broader emotional and interpersonal skills that will help them throughout life.

“I appreciated and was perhaps inspired by the authors’ ability to write a book and then relate it to others … That whole process spoke to me.”

– Michael Hughes ’13

“It was very moving for me personally to see how influential the program was,” Sagan said in 2013. As two-time Stanford parents, he and his wife, Sujitpan Bao Lamsam, perceived so much value in the program that they endowed it in 2013.

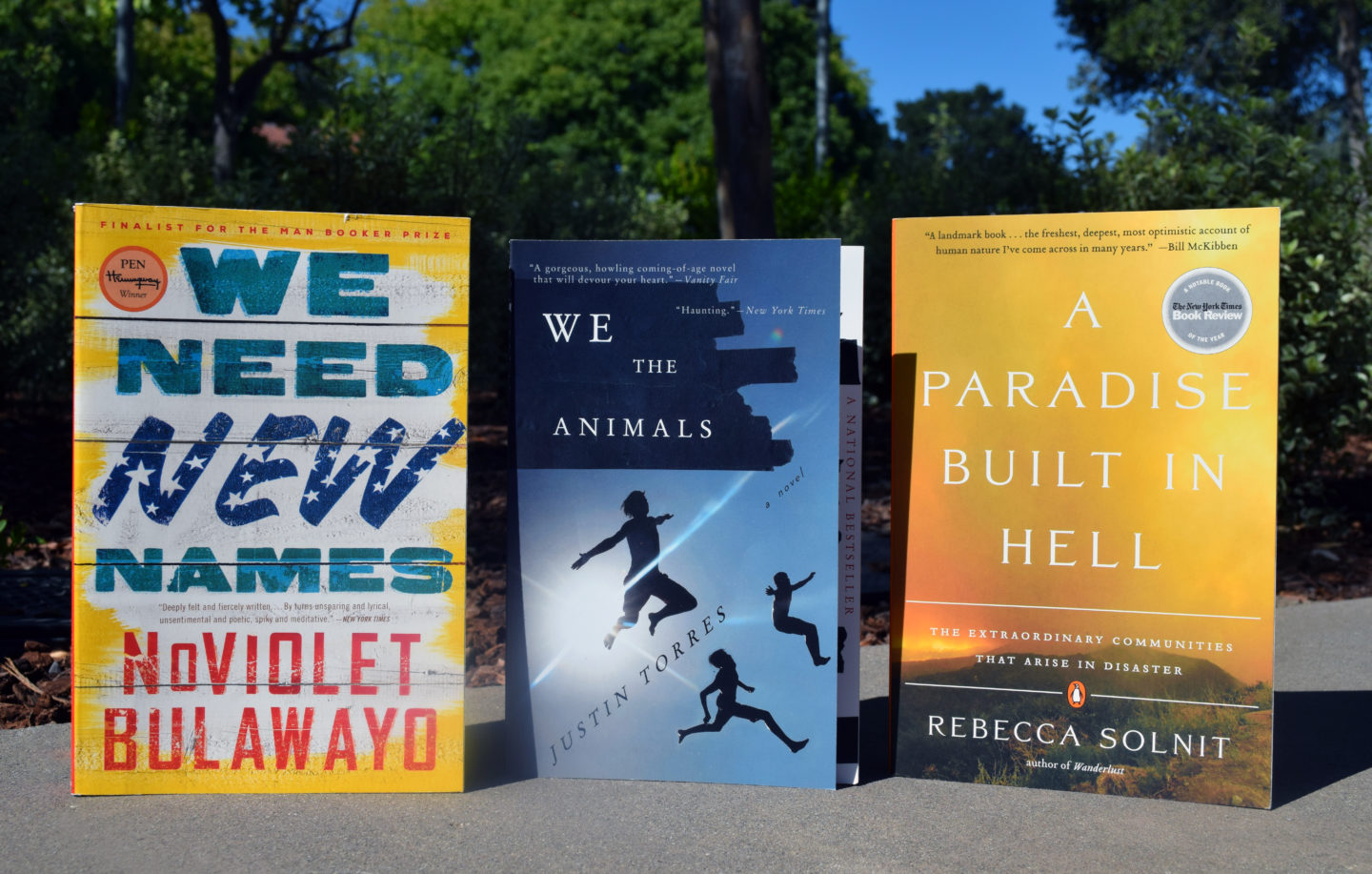

This year’s moderator, English Professor Elizabeth Tallent, chose books on the theme of crisis and connection: NoViolet Bulawayo’s We Need New Names, Rebecca Solnit’s A Paradise Built in Hell, and Justin Torres’ We the Animals.

Each book “engages with trauma and each are about a reckoning with crisis. They each have their share of darkness, and they’re each about coming through,” Tallent said in this video. “And at the very deepest level, piecing together a community.”

In discussing the books, students translate the private discussion between author and reader to a larger one, “a community linked by … conversations,” Tallent wrote to incoming students. They learn another important value of Stanford life: that members of the community learn with and from one another.

Pre-major advisers receive the books, too, so they can use them as tools to engage students in discussions about goals, values and future careers.

University President John Hennessy moderated Three Books in 2015, selecting English Prof. Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life, Lalita Tademy’s Cane River and Walter Isaacson’s The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution.

Hennessy said he chose the books because each one provides invaluable insights about resilience and determination – lessons that will serve students well at Stanford and throughout their lives.

“In This Boy’s Life, Toby has to face and survive a dysfunctional home life, while Cane River relates tales of survival and even personal triumph in the face of slavery and racism,” Hennessy told the Stanford News Service. “Isaacson’s Innovators focuses on the skills of collaboration, innovation and persistence that are needed to achieve something exceptional.”

Choosing the Three Books isn’t easy. Engineering Dean Persis Drell said she took months to make her selections for the 2014 event, even with the help of a focus group of undergrads convened by the Vice Provost of Undergraduate Education.

“I spent two months searching for the third book, and it was really, really hard,” Drell told the Stanford News Service. She settled on the novel My Year of Meats. The tale of a videographer hired to promote American beef consumption in Japan had Drell “laughing out loud” but underscored her conviction that “almost all aspects of our daily lives … are touched by modern science.”

Nor are the Three Books always texts as such. In 2008, Professor Andrea Lunsford, then director of Stanford’s Program in Writing and Rhetoric, and Julie Lythcott-Haims, then dean of freshmen, included Lynda Barry’s graphic fiction One! Hundred! Demons! in their program on youth, choice and self-identity.

In 2012, Music Associate Professor Mark Applebaum chose only one book, Metal Odyssey in Rural Nörth Daköta by Chuck Klosterman,plus a DVD of the film My Kid Could Paint That and the iPhone apps MadPad, Ocarina and I Am T-Pain.

Using works other than books “was liberating,” Applebaum told Stanford Magazine, “allowing for questions about what we learn from different types of texts, whether they are a book, a film or a tool.”

As time goes by, the Three Books work on their readers in sometimes unexpected ways. Michael Hughes ’13 had no intent of becoming a writer himself as he sat in Memorial Auditorium listening to the Three Books authors in September 2009.

“Later on, I appreciated and was perhaps inspired by the authors’ ability to write a book and then relate it to others – speaking about it, explaining their motivations or creative impulses,” Hughes said. “That whole process spoke to me.”

Today, Hughes is a mortgage analyst and the author of two published novels. He writes regularly, in a practice he began in mind of 2009 Three Books author Malcolm Gladwell’s “10,000-hour rule.”

Browse all the works chosen since the program’s inception in 2004.

Watch Tallent’s video about the 2016 selections.