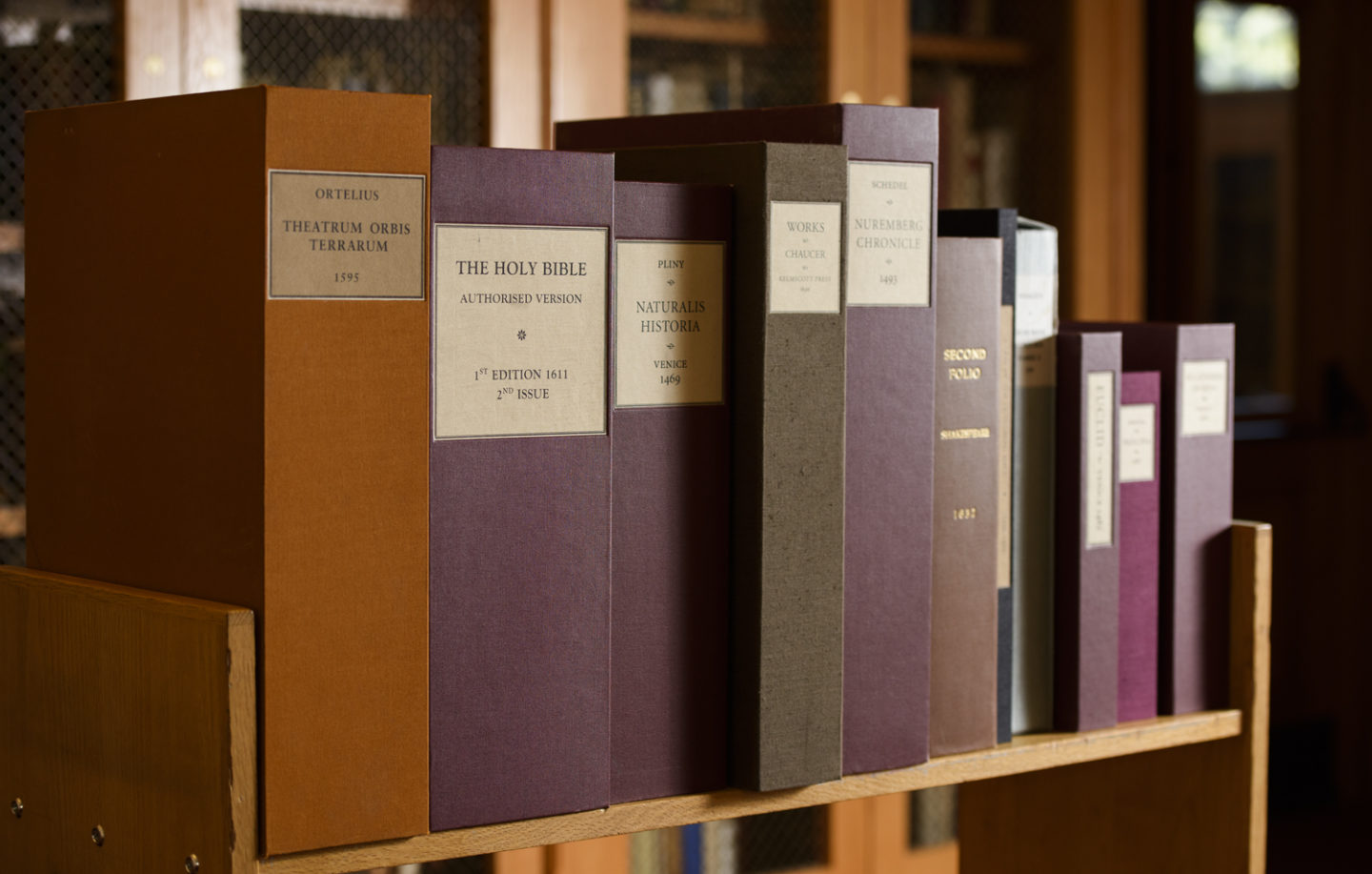

Milestones in knowledge, they reveal how printed books began

Among the millions of books in the Stanford Libraries are some of the world’s rarest and most celebrated. Some, such as the 1611 King James Bible and Shakespeare’s Second Folio, are priceless for the language they contain.

Others tell a story of the printed book as innovation. Milestones in typography, layout, design, and organization, and even in market demand, they reveal how books evolved in the 15th and 16th centuries as printers refined their delivery of the Western world’s expanding knowledge.

The first book to use italics, the first printed book of mathematics and the first modern atlas are all held by Stanford.

John Mustain, curator of rare books at the Stanford Libraries, shares 12 of his favorite books in the Libraries’ Special Collections – and a leaf from a 13th – and explains what makes them special.

1. Signs of books to come: A portable manuscript Bible

Manuscript on vellum. France, 13th century

This is not a grand or famous Bible. Rather, it is a fine example of a typical 13th-century French portable Bible, a genre revolutionary in its time and crucial in the history of Bible production and of books in general. It was produced in or near Paris, the text following the standard Parisian sequence of the time, and it is extensively illuminated.

The relatively small script used for the text was revolutionary. A 12th-century Bible typically had the text in a large and bold hand, with notes, or glosses, at the sides in a tiny script and with many abbreviations. This Bible’s tiny and heavily abbreviated script was recognized as ideal for the text of a small-format Bible. The hand once used for glossing the Bible was now used for the text itself.

The result was an entirely new look for the Bible. For the first time, the entire work could routinely be bound in a single, portable volume, a significant change in book production in the west. Bibles such as this volume in the Stanford collection were relatively common in the 13th century. Their size and portability endured into the modern era.

The other revolutionary aspect of this 13th-century Bible lies in its ordering of the books. It generally follows the Greek rather than the Hebrew tradition. With a few exceptions (e.g., the Book of Acts is placed in these Bibles after the Pauline Epistles and before the Catholic Epistles), it survives today.

2. From the West’s first typeset book: A leaf of the Gutenberg Bible

Mainz: Johann Gutenberg, 1454–1455

The first book printed in the Western world by means of movable type, the Gutenberg Bible is justly celebrated.

It is a large book, modeled on the manuscript lectern Bibles of its day. Just as contemporary biblical and liturgical manuscripts were written in a gothic script, the Gutenberg Bible was printed in a gothic type, and a handsome type it is – attractive, compressed, upright. As most of its pages contain 42 lines, it is often referred to as the “42-line Bible.” The overall effect is elegant, beautiful and massive, the letters crisp and dark on the page.

This leaf is printed on paper, though many copies of this Bible were printed on vellum (animal skin). The text is from Ezra 4-5; Esdras in Latin. The “es” portion of the name is visible in red and blue at the top of the page. The Roman numeral V in blue denotes the fifth chapter, which begins De signis, with the initial capital letter in red. The first letter of each sentence is highlighted with a red stroke. All of this color adornment was done by hand.

3. Compiling human knowledge: Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia

Venice, 1469

Pliny’s Natural History was the first scientific book to be printed and one of the most influential books – scientific or otherwise – ever printed. This first-century Roman’s ambitious undertaking was to produce an encyclopedia of all the knowledge of the ancient world.

He quotes more than 400 authorities and includes material on animals, plants, stones, metals, botany and geography. Pliny’s compilation soon became a standard work of reference, with abstracts and abridgments appearing as early as the third century. It survived in many manuscript copies during the Middle Ages and was printed in some 18 editions before 1501. The 1469 edition in Stanford’s collections had a print run of only 100 copies.

In a letter to Tacitus (ca. 106), Pliny’s nephew movingly recounts the author’s death in 79. Pliny the Elder had sailed to the beach near the eruption of Vesuvius that buried Pompeii and Herculaneum. He went to observe the phenomenon and to rescue a friend, and became another victim of the disaster.

4. Mathematics in print: Euclid’s Elements

Venice, 1482

This is the first edition of the first mathematical book ever printed, as well as the first major work to be illustrated with geometric diagrams. It is one of the loveliest books printed in the Renaissance.

5. Lavish history: Hartmann Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle

Nuremberg, 1493

The Liber Cronicarum, popularly known as the Nuremberg Chronicle, is an illustrated history of the world from creation to the 1490s. It was compiled by Hartmann Schedel, printed by Anton Koberger and illustrated with woodcuts by Michael Wohlgemuth, Wilhelm Pleydenwurff and likely Albrecht Dürer.

It tells the story of human history as related in the Bible, and includes accounts of natural catastrophes, histories of several Western cities, and genealogies, among other topics.

The chronicle was the most lavishly illustrated book of its day, with 1,809 illustrations from 645 woodcuts, many of which were used repeatedly. For example, the same woodcuts were used as images for various cities. The illustrations blend beautifully with the text, which in some cases was deliberately wrapped around a woodcut. The book includes a large index, unusual for the time.

It was translated from Latin into German as early as 1493, and reprinted in both languages before the end of the century – a monumental task of printing, but fully justified given the book’s popularity and importance.

6. Impenetrable fantasy: Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (The Strife of Love in a Dream)

Venice, Aldus Manutius, 1499

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, with its enigmatic text, is the most celebrated illustrated book of the Renaissance, a masterpiece of book production, with a remarkable blend of lovely woodcuts and fine printing.

The book features Poliphilo and his quest for his beloved, Polia, a search that serves as a vehicle for a discussion on gardens, architecture and aesthetics, among other things. It was produced by Aldus Manutius (ca. 1450–1515), the most famous printer of his day. The roman typeface used in Hypnerotomachia is still praised as one of the most beautiful ever produced, both handsome and legible.

7. First use of italics: Letters of St. Catherine of Siena (1347–1380)

Venice, Aldus Manutius, 1500

The frontispiece, a woodcut illustration of St. Catherine, includes the first appearance of italics in a printed book.

In the 16th century, Aldus and his press would famously and successfully become the first printing house to use this style of lettering.

Italic type was modeled on the humanist cursive of the day. It is elegant and compact, and allows more words per page, not an insignificant consideration in printing, as the cost of paper was the most expensive single cost in producing a book. Only later were italics used for emphasis or differentiation. The Aldine edition of Virgil (1501) is recognized as the first book to be printed throughout in italic.

8. Human anatomy illustrated: Andreas Vesalius’ De Humani Corporis Fabrica

Basel, 1543

A masterpiece of anatomical description and design and a monument of Renaissance science. The splendid illustrations established new standards for anatomical images. The book’s emphasis on dissection of humans – rather than animals, as had been traditional – greatly furthered the knowledge of human anatomy.

9. First modern atlas: Abraham Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum

Antwerp, 1595

Travel and exploration expanded rapidly in the 15th and 16th centuries, and Ptolemy’s Geography had been rediscovered in 1410. These developments stimulated the demand for accurately drawn maps of both the Old World and the New.

In the 1560s, the Flemish cartographer and publisher Abraham Ortelius began to assemble maps of all areas of the world, with an eye toward publishing them. These maps would be published in 1570 as Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. It is the first modern atlas, a single volume with each map on one full sheet and with supplementary text.

Ortelius continued to add to his own atlas. In the 1570 edition, there were 53 maps. By this 1595 edition, there were more than twice that number.

10. First edition of the King James Bible

London: Robert Barker, 1611

The Holy Bible, Conteyning the Old Testament, and the New: Newly Translated out of the Originall Tongues: & with the Former Translations Diligently Compared and Reuised, by His Maiesties Speciall Comandement.

Known variously as the King James Bible and the Authorized Version, this remarkable text was produced by more than 40 scholars who labored for years, working from previous English translations of the Bible and texts in the original languages.

John Reynolds (1549–1607), of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, proposed this new translation at a conference of the High Church and Low Church parties in England, convened by James I in 1604. The revisers, drawn from the most eminent scholars of the day, were divided into teams, with each team assigned various books of the Bible. Each team’s revisions were submitted to others for critical review.

Responsibility for printing the new Bible was given to Robert Barker, “printer to the Kings most Excellent Maiestie.” As befitted such a grand success of the Church, the Crown and the university scholars, the first edition was issued in this large folio in 1611.

The translation exudes brightness and richness, and remains without question one of the pinnacles of the English language. It was generally accepted as the standard edition of the Bible in English until the Revised Standard Version appeared in the mid-20th century.

11. The second folio edition of Shakespeare

London, 1632

This 1632 edition includes some careful editing of the 1623 text, the first folio edition. Many of the textual changes were improvements, though new errors crept in during printing.

It is also notable for the laudatory poem at the beginning of the work – the first appearance in print of a poet named John Milton, age 24.

In many ways this book is a reprint (it calls itself “the second impression”) of Shakespeare’s 1623 first folio, which William Jaggard in Shakespeare Bibliography described as “the most priceless contribution, beyond all bounds and limits, to the whole world’s secular literature, and to those giant forces which promote the welfare of humanity.”

12. Founding Fathers’ touchstone: John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Dublin, 1751

This copy of an otherwise unremarkable edition of Milton’s great epic poem is rendered spectacular by bearing the signatures of both Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. It is the only copy of any book known to be signed by both men.

John Milton had been Oliver Cromwell’s Latin secretary and a republican theorist during the English Commonwealth period. He was viewed sympathetically by many American revolutionaries. Jefferson entered numerous quotations from Paradise Lost in the literary commonplace book he kept in his youth. Later, he quoted Milton extensively in his essay “Thoughts on English Prosody.”

Jefferson may have loaned this volume to James Madison, who signed his name on the title page and four times on the title-page verso, the latter while striving to draw ink into the quill. This may have vexed Jefferson, for Madison’s signature on the title page has been almost completely erased, and Jefferson has signed the title page himself, which was unusual: Jefferson typically used other means to identify his books. The pencil signature of James Maury, a close friend of Jefferson’s, appears on the dedication page.

13. Inspiration from the past: William Morris’ Kelmscott Chaucer

London, 1896

A British bibliophile, craftsman, designer, writer and typographer, William Morris (1834– 1896) was a major figure in the Arts & Crafts movement of the late 19th century.

This loosely linked group of artisans, craftsmen, architects and writers sought to elevate the status of the applied arts. Morris looked to the past for inspiration, founding the Kelmscott Press and endeavoring to reproduce books in the style and appearance of books from the first century of printing.

The Kelmscott Chaucer is Morris’ best-known work. The woodcut illustrations epitomize what his circle saw as the style and high moral tone of medieval design and illustration.